I’m not an expert on Jewish prayer, or on Hebrew language or grammar. Far from it. But sometimes a single word captures my attention, and I spend a lot of time puzzling over what it means to me.

Sometimes it’s just a comma—or the absence of one.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about part of the prayer known as Ahavah Rabah, which translates as “abundant love.”

The prayer begins:

With abundant love you have loved us, Lord our God. With great mercy you have been merciful to us.

Okay, we’re expressing gratitude and, as you might guess, working up to a request. The prayer continues:

For the sake of our ancestors who trusted you, and to whom you taught the laws of life, so grace us and teach us.

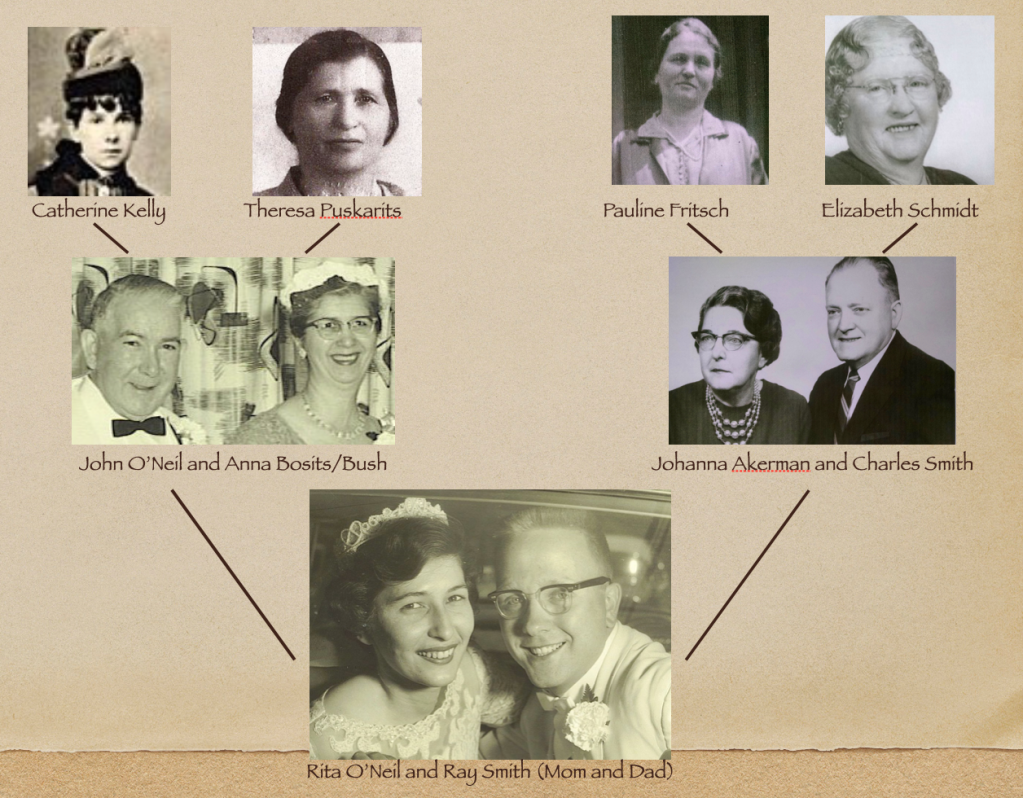

The word that grabbed me here is “ancestors.” The Hebrew is avoteynu, which literally means fathers or patriarchs. Modern translators often consider it to be gender-inclusive. But some egalitarian prayerbooks add the parallel feminine word, imoteynu, yielding “our patriarchs and our matriarchs,” or “our fathers and our mothers.”

Avoteynu was good enough for me until a few years ago. That’s when I identified my very own Jewish ancestor—my great-grandfather Bernard Akerman—and learned the names of his parents.

Continue reading